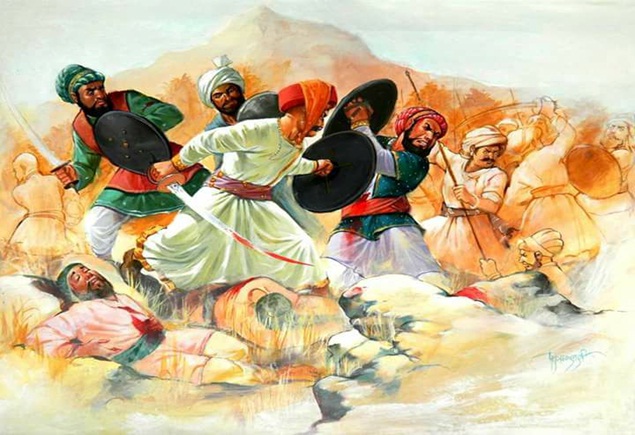

14 January 1761 – ‘THE BLACKEST DAY IN INDIA’S HISTORY’ – Third Battle of Panipat

By Col Ajay Singh (Veteran)

14 January 1761 – the auspicious day of Makar Sankranti – was the “Blackest Day in Indian History”. On this day, 50-60,000 Marathas fell during the Third Battle of Panipat. Another 20-30,000 women and children were captured and taken as slaves, and the Maratha Empire received a death blow from which it could never really recover.

The roots of the battle can be traced to the rise of the Maratha Empire and which brought it into conflict with the Durrani empire of Ahmad Shah Abdali in Afghanistan. By 1755, the Marathas were the dominant power of the sub-continent. Its influence encompassed the Deccan, most of Northern India and even Calcutta. In 1759, a Maratha expeditionary force had reached Kandahar in Afghanistan and they had established garrisons in the major cities of Punjab.

The rise of the Marathas was viewed with fear by the Muslim rulers of North India. Led by Najib-ud-Daulah of Rohilkhand (modern day Western UP) and Siraj-ud- Daulah of Awadh, they invited Ahmad Shah Abdali to wage ‘jehad’ against the Marathas. The call was sweetened by a purse of Rs 2 Crores and after his initial hesitations, Abdali decided to come to India to contest the Marathas.

Abdali entered India through the Khyber Pass in January 1760. His armies brushed aside the Maratha garrisons in Punjab and forced them to withdraw. He then moved his armies to Anoop Shahr (around 70 kilometers east of Delhi near Saharanpur), in the kingdom of his ally Najib- ud- Daulah, and camped there awaiting the Marathas.

The arrival of Abdali and the defeat of their garrisons had worried the Marathas and in March 1760, the Peshwa Nanasaheb, decided to send a large expeditionary force under his most capable general – Sadashiv Rao Bhau – and his own son, the 17 year old Vishwas Rao to contest Abdali.

The Maratha army left Udgir on 07 March 1760, with around 40,000 cavalry, 15,000 troopers and around 200 pieces of artillery. It was joined along its advance by forces from the Holkars of Indore and the Scindias of Gwalior. Yet in spite of its size, it was ill-equipped and lacked administrative support. The army was told to live off the land as it advanced, a strategy that led to looting and pillaging of the countryside over which it advanced and earned it much antagonism in its northwards move. The army was also encumbered by the presence of around 15-20000 ladies and children and camp followers, which slowed the advance of the army as it moved slowly over three months before it reached Delhi on 21 July.

The Marathas captured Delhi easily and ransacked it, camping there for over three months. The army of Abdali and his allies were in Meerut – Saharanpur, the two armies separated by the Yamuna River. Though patrols and skirmishes were frequent no major clash of arms took place as yet.

Then at the end of October Sadashiv Bhau led his army out of Delhi and moved towards Kunjpura, a fortress on the west bank of the Yamuna which was a major supply hub of Abdali. Kunjpura was strongly held with over 10,000 Afghans but was captured in just two nights after an intense attack using artillery and cavalry in close coordination. Abdali and his army were on the opposite bank of the river and though Abdali could see and hear the plight of his men, he was unable to cross the flooded Yamuna river to aid them.

Kunjpura fell on 18 October and was the last major success of the Marathas. They now had access to Abdali’s supplies and better still was in a position to block his return to Afghanistan. Bolstered by this success, the Marathas moved further towards Kurukshetra hoping to block Abdali’s return route completely. Then Abdali launched his masterstroke. On a rain-swept night on 25 October, he crossed the swollen Yamuna River. Even though over 200 soldiers were swept away, his entire army got across over two nights completely taking the Marathas by surprise. The tables were now turned. Abdali was now behind the Marathas and had cut off from their route back to Delhi and the Deccan.

With their escape routes blocked, the Marathas established a camp in the vicinity of Panipat. For three months, the Marathas remained besieged within their camp. Disease and starvation was rampant as they were cut off from their supplies. Skirmishes took place almost on a daily basis causing heavy casualties on both sides. Worse, winter was setting in and the Marathas were ill-equipped and unprepared for the North Indian winters.

With their strength weakening, Sadashiv Bhau called for a meeting of his Chiefs on 12 Jan and the War Assembly decided that rather than remain besieged, they would make one concerted attack to break through the Afghan positions and make their way back to Delhi and thence the Deccan. Ceremonial paan was served as a gesture of farewell, the Quartermaster was ordered to distribute the remaining food amongst the troops and the chieftains went to prepare their men for battle. The die was cast for the most decisive battle in India’s history.

The Bloody Makar Sankranti

At dawn on 14 January 1761, the Maratha army moved out of its camp to the sound of conches and ranbakuras. Around three to four kilometers opposite them, the Afghans had arrayed in battle formation with a force of around 60,000 cavalry, infantry and artillery. Yet more than the numerical superiority of over 20,000 which the Afghans enjoyed, what made the difference was that Abdali’s army was a well-knit, cohesive force with the disparate chiefs held together by the iron personality of Ahmad Shah Abdali. On the other side, the Marathas were riven by dissension, with their chiefs often at loggerheads with each other. The divisions would come to the fore as the battle progressed.

The Marathas attacked first from their left flank – an attack led by Ibrahim Khan Gardi, a Muslim chief who would be one of the heroes of the battle. It was an ordered, disciplined attack with nine battalions, with one moving forward as the other gave fire support. The attack made slow, but gradual progress, and inflicted heavy casualties on the Afghan right flank opposing them. Then the Marathas made their first mistake.

As per the plan, Gardi’s musketeers were to establish a foothold in the Afghan lines and then the Maratha cavalry was to attack from the flank. Yet even as Gardi’s troopers were inching forward, the Cavalry attacked pre-maturely moving ahead of Gardi’s infantry and preventing them from firing. The cavalry assault which should have given a decisive edge in the initial stage of the battle petered out, but in spite of that, a breach was made in the Afghan right flank by around noon.

Simultaneously with the attack of his left flank, Sadashiv Rao Bhau had launched the main attack with around 20,000 crack troops – the Huzarat – directed at the Afghan center. He led the attack himself and its sheer force and momentum tore through the Afghan center causing them to break in disarray.

Around midday, the Marathas were well poised. They had broken through the right flank and the Center. Their right flank, under Holkar and Scindia, were to have attacked after the Afghan lines were breached, but inexplicably they did not move. They remained static even though Sadashiv Bhau sent a personal message to Holkar. The reluctance of their right flank to attack cost the Marathas dear. It gave time for Abdali to position his military police to round up all who were fleeing the battle and send them back to the front lines (with a few summary executions of those who refused). He also sent around 10,000 of his reserves to reinforce the crumbling lines. By around 2 pm the Afghan lines were steadied and any hope of a Maratha breakthrough vanished.

The Maratha attack petered out and Abdali launched a counter stroke from his own left flank behind the Marathas. His cavalry and ‘Zamburaks’ – camel mounted swivel guns poured a relentless stream of fire on the Marathas, who were gradually being compressed in a tight knot ahead of the Afghan positions. Afghan bullets took a deadly toll on the bunched Maratha infantry and one of the bullets hit Vishwas Rao, the Peshwa’s son on the head killing him instantly.

The death of Vishwas turned the battle dramatically. Seeing him fall, the troops lost heart. Sadashiv Bhau himself dismounted from his elephant to come to see Vishwas and without his rallying presence, the Marathas troops panicked and began fleeing the battlefield. In the unruly chaos that followed, Abdali launched another attack with the rest of his reserves that swung in from the rear and sides of the beleaguered Marathas.

What followed was a slaughter. Weakened after the day-long fighting they were cut to pieces as the Afghan cavalry tore into them and bullets rained upon them. Their right flank under Holkar and Scindia took no part in the fighting and melted away from the battlefield, moving to Delhi and then their home bases. For the rest, it was carnage, as they battled desperately in isolated pockets. Over 30-40,000 Maratha soldiers fell that day alone (another 20,000 had been lost in the skirmishes of the preceding months). The vengeful Afghans who had lost around 30,000 of their own, ran amok in the Maratha camp, slaughtered the menfolk and took the women and children as slaves. That night, the moon was full and the fleeing Marathas were chased and cut down in the open fields around Panipat. An estimated 60-70,000 lives were lost in that one day which has often been called ‘The Bloodiest Day of the 18th Century”.

Of the estimated force of 70- 80,000 that set out, only around 15,000 or so succeeded in making their way back to the Deccan. Abdali left back for Afghanistan soon after the battle, receiving hefty compensation from the Muslim rulers. The Peshwa died of shock after the disaster and Maratha power now waned. Its decline set the stage for Imperial rule in India. Devoid of any major challenger, the British consolidated their position and established British rule in India that would last 200 years. That perhaps was the greatest tragedy of the battle.

(Ajay Singh is a noted writer who has authored five books and over 200 articles. He has recently been awarded the Rabindranath Tagore International Prize for Art and Literature 2021.)