Need to put in place a ‘Grow in India’ programme to transform the socio-economic fabric of our agricultural sector: Vice President

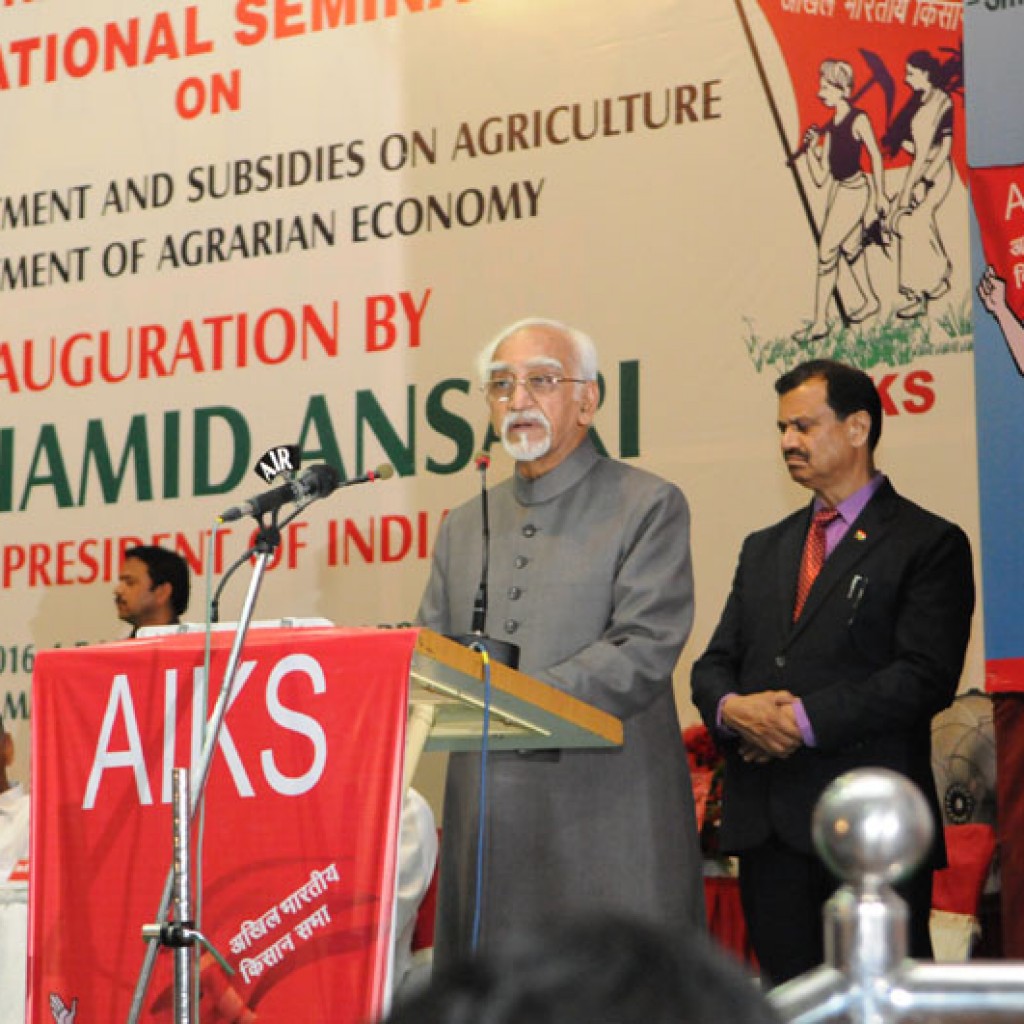

The Vice President, Shri M. Hamid Ansari addressing the National Seminar on 'Public Investment and Subsidies on Agricultural Inputs and the Upliftment of Agrarian Economy', in Hyderabad on March 05, 2016.

The Vice President, Shri M. Hamid Ansari has said that we need to put in place a “Grow in India” programme to transform the socio-economic fabric of our agricultural sector. He was delivering, here today, the keynote address at the National Seminar on ‘Public Investment and Subsidies on Agricultural Inputs and the Upliftment of Agrarian Economy’, organized by the All India Kisan Sabha which was attended by farmers from all over the country.

The Vice President said that the government needs to take bold steps to translate the good intentions into action to tackle the deficiencies in farming. This would, however, require a strong political will and the need to develop a wide political consensus, he added. The Vice President further said that we need a social corrective along with the economic correctives to redress these challenges in development of rural sector. Mere infusion of funds might not be enough unless the underlying social gaps and divisions remain in place, he added.

The Vice President said that the centrality of Agriculture in the socio-economic fabric of India is self evident and almost half of the workforce in India still remains dependent on agriculture. He said that the issue of farmer’s suicides is certainly a complex one but it brings into sharp focus the stresses that the agricultural sector in India is now subject to. He further said that there are indications that the Green Revolution benefits have plateued.

The Vice President observed that small farms are weak in terms of generating adequate income and sustaining livelihood. Their participation in agricultural market remains low due to a range of constraints such as low volumes, high transaction costs, lack of markets and information access, he added.

The Vice President said that the enhanced public expenditure in agriculture – in form of increased investments, rather than un-targeted subsidies – is required to bring about technical change in agriculture, and higher agricultural growth.

Following is the text of Vice President’s address:

“I thank the organizers of this relevant seminar for inviting me today.

We gained our independence in August 1947. Freedom came in the wake of the great, man-made, Bengal Famine of 1942-43 which claimed about 3 million victims. In the early years of freedom, food shortages were rampant, dependence of food imports was perennial, and food rationing was regularly resorted to. For this reason, Jawaharlal Nehru said in 1948 that ‘everything else can wait but not agriculture’. In 1951-52, the total grain production was 52 million tons. Today, it is over 264 million tons.

The centrality of Agriculture in the socio-economic fabric of India is thus self evident. As a source of livelihood, agriculture – including forestry and fishing- remains the largest sector of Indian economy. While its output fell from 28.3% of the economy in 1993-94 to 13.9% in 2013-14, the numbers employed have declined only from 64.8% to 48.9%. Therefore, almost half of the workforce in India still remains dependent on agriculture.

Agriculture is also a source of raw materials to a number of food and agro-processing industries. It is estimated that industries with raw material of agricultural origin accounted for 50% of the value added and 64% of all jobs in the industrial sector. At $38 billion, agricultural export in 2014-15 constituted 10% of our exports.

After independence, we undertook special programmes such as the Grow More Food Campaign and the Integrated Production Programme focused on improving food and cash crops supply. Land-reforms were undertaken with two specific objectives. First- to remove impediments to increase in agricultural production arising from the inherited agrarian structure; and Second- to eliminate elements of exploitation and social injustice within the agrarian system, to provide security for the tiller of soil and assure equality of status and opportunity to all sections of the rural population.

Successive Five Year Plans stressed self-sufficiency and self-reliance in food-grain production. Concerted efforts in this direction did result in substantial increase in agricultural production and productivity. This was the ‘Green Revolution’.

Today, India is the largest exporter of rice in the world, and the second-largest exporter of buffalo meat and cotton. India is the largest producer of milk, and the second-largest producer of fruits and vegetables, rice, wheat and sugarcane.

There are, however, indications that the Green Revolution benefits have plateaued. There is criticism that the input intensive approach has largely been irrelevant for 60% of India’s cultivable land which is un-irrigated. These rain-fed areas have failed to benefit from public spending despite the fact that 90% of the country’s oilseed, 81% pulses and 42% food grains are produced here.

Since the early 1990s, liberalization and globalization have become central elements of development strategy of the government. This has also had an impact on Indian agriculture. Such measures were aimed at creating a potentially more profitable agriculture sector, which could ‘bear the economic costs of technological modernization and expansion’.

The reforms appear to have improved terms of trade for agriculture but growth in agricultural sector has been weak and well below that of non-agricultural sectors. The gap between rural and urban incomes has widened. While national income has grown at above 6% over the last five years, agricultural income grew by mere 1.1% during 2014-15.

A survey commissioned by Bharat Krishak Samaj on ‘The State of the Indian Farmer’ in 2014 reported that some 62% of Agriculturists were willing to quit farming to move to cities and that only 20% of the rural youth was keen on continuing farming. The survey found that more than 40% farmers were dissatisfied with their economic condition. The figure was more than 60% in eastern India. These are disturbing trends.

Since 1995, some 300,000 farmers have committed suicide in the country. According to P. Sainath, ‘suicide rates among Indian farmers were a chilling 47 per cent higher than they were for the rest of the population in 2011.’ The issue of farmer’s suicides is, no doubt, a complex one but it brings into sharp focus the stresses that the agricultural sector in India is now subject to. The recent mobilization- in support of demands for caste based reservations in government jobs, and not for betterment in Agro sector- by communities that have traditionally benefitted from Agriculture- also indicates the growing stress within Indian agriculture.

Some policy experts have noted that public fund allocation to Agriculture remains substantial. Of the five concerned Ministries related to agro-sector- Agriculture, Chemical and Fertilizers, Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, Food Processing Industries, and Water Resources- for 2015-16 was roughly Rs 2.3 lakh crore. This is not a paltry sum.

Why is the Indian Agriculture under such stress despite the quantum of public investments it appears to be receiving?

It has been observed that small farms in India are superior in terms of production performance but weak in terms of generating adequate income and sustaining livelihoods. Small and marginal farmers, whose land holdings are below 2 hectares, constitute almost 80% of all Indian farmers, and more than 90% of them are dependent on rain for their crops. Their participation in agricultural market remains low due to a range of constraints such as low volumes, high transaction costs, lack of markets and information access.

This disparity is illustrated starkly by the experience from Punjab- a state which has undergone substantial modernization of the agricultural sector. There was consolidation in the land holdings and the subsidization of fertilizers and electricity for irrigation. Per hectare consumption of fertilizers increased and water intensive crops like cotton and rice were adopted. Studies have shown that the total operational cost of rice and wheat production increased by around 50% between 2000-2001 and 2005-2006, while rice yields increased by only 12%, and wheat yields actually declined by 8%. Thus, while farmers invested more on growing their crops, their total output, and therefore their profit, continued to decline. As the water tables have fallen, only farmers who were able to afford more powerful- and more expensive- equipment have been able to use the subsidized electricity for irrigation. The subsidies on fertilizers have also resulted in the unrestricted use of chemicals leading to salinization and Nitrogen-nutrients imbalance in formerly fertile soils.

The Economic Survey for 2015-16 includes a detailed analysis of fertilizer subsidy and its associated inefficiencies and misuses. Rs 73,000 crore, amounting to 0.5% of the GDP, was budgeted for fertilizer subsidy. However, the Survey highlights three types of leakages for urea alone. First, it points out that 24% of the urea subsidy goes to inefficient producers of urea manufacturers; second, of the remaining urea subsidy, 41% is diverted to non-agricultural uses and is smuggled to neighbouring countries; and third, most of the remaining 24% is consumed by large farmers. So, in a nutshell, only 35% of the urea subsidy goes to intended beneficiaries- the small and marginal farmers. The Survey suggests taking the direct benefits transfer (DBT) route via JAM – Jan Dhan, Aadhaar and Mobile- and de-canalising imports of urea. Agricultural experts agree that this is a ‘fertile candidate for reform’.

Agriculture in India intersects with almost every development agenda—be it human development, poverty elimination, rural development or environmental protection. Agricultural capacity has a direct impact on the food security situation in the country. It also helps in initiating and sustaining demand in other sectors. A progressive agriculture sector, thus, serves as a powerful engine of economic growth.

The 12th five year plan growth target for agriculture sector had been set at 4%. The Gross Capital Formation in agriculture and allied sectors as percentage of total GDP has remained stagnant at less than 3%. Public spending on agriculture research, education, and extension is presently about 0.7% of agricultural GDP- much lower than the international norm of 2%. This raises concern that the inadequacies of the provision of the critical public goods for Agriculture may dampen the targeted growth.

In a recent essay, Ashok Gulati, former Chairman of the Commission on Agricultural Costs and Prices, has noted;

“Agriculture needs massive investment, for irrigation, agri-R&D and to build faster and more efficient value chains between farmers and retailers. Irrigation alone may need more than Rs 3,00,000 crore if it has to be provided to every farmer. But the Ministry of Water Resources was allocated only Rs 4,232 crore for Financial Year 2016, less than the revised estimate of Rs 6,009 crore for the previous year…….At this pace and with such allocations, irrigation for all farmers by 2022 — promised to them by the PM — looks like a distant dream.”

Enhanced public expenditure in agriculture- in form of increased investments, rather than un-targeted subsidies- is thus required to bring about technical change in agriculture, and higher agricultural growth. In addition, concerted reforms are needed to achieve equity in terms of higher growth in disadvantageous regions like rain-fed and tribal areas and benefit small and marginal farmers.

Some of the areas for policy intervention may include the following;

1. Land market reforms are in need of a new impetus. As holdings are becoming fragmented and uneconomical, marginal farmers need flexibility in leasing out the land. There is perhaps a need to have a framework for operation of land markets but with sufficient safeguards to protect interest of small and marginal farmers.

2. Agricultural price policy has been facing challenges. The practice of announcing minimum support price based on variable costs before sowing season could be looked into. Similarly, procurement price based on total costs may be used to procure foodgrains needed for public distribution system (PDS) and for food security purpose.

3. We need to consider a rational approach to pricing of agricultural inputs such as irrigation, power and fertilizer. However any such measure, while providing timely delivery of the required inputs, must ensure that the small and marginal farmers are not adversely affected.

4. Farm and food subsidies need to be rationalized and better targeted to benefit the poor and the needy. Direct cash transfers offer a possible mechanism. While ensuring transparency and preventing leakages is important, these subsidies are justified as they benefit not only producers but the society at large. Large subsidies continue to be provided by developed countries that has distorted the international food prices. OECD data shows that their members spent around $258 billion to subsidize agriculture in 2013. European Union spending on farm subsidies accounts up to $ 58 billion annually.

5. Although flow of agricultural credit has increased significantly in recent years, we need to address distributional aspects of agricultural credit including better access to small and marginal farmers, strengthening rural branches and reducing significant regional and inter-class inequalities in credit.

More than 800 million of India’s 1.3 billion people live in rural areas. One quarter of this population lives below the official poverty line. The search for economic justice for a population of this magnitude cannot be addressed by relying on migration to the cities. Rural-urban migration and absorption of labour in the urban economy has been slow due to the slow growth of employment in manufacturing. The rural labour force will therefore have to find a way to improve their incomes in situ. Strengthening of agriculture, thus, becomes a national imperative.

Amartya Sen in his seminal ‘Development as Freedom’ argues forcefully that democracy plays a pivotal role in ensuring that indicators of abject poverty such as famines do not occur in such societies due to the presence of a free media and a political class that has to be necessarily responsive to citizens needs. Harvard Professor Ashutosh Varshney raises some questions as to why the Indian farmer, despite having the democratic numbers, failed to secure a better economic deal from the Indian state. Varshney attributes this to the ‘self-limiting’ nature of rural politics in India;

“for rural power to push the state in economic policy more in its favour, it must present itself as a cohesive force united on economic interests – higher producer prices, larger subsidies and greater investment. Rural India has chosen not to construct its interest entirely economically. While politics based on economic demands is stronger than before, politics based on other cleavages – caste, ethnicity, religion – continues to be vibrant. Politics based on economic interests potentially unites the villagers against urban India; politics based on identities divides them, for cast, ethnicity and religion cut across the urban and the rural. There are Hindu villages and Hindu urbanities just as there are ‘backward castes’ in both cities and villages. Until an economic construction of interest completely overwhelms identities and non-economic interests, rural power, even though greater than before, will remain self limited.”

Describing the developmental challenges in our rural sector, Rajiv Lall had noted that; “The truth is unfortunately more complex and less comforting. As impressive as the ongoing transformation of rural India seems to be, a number of old challenges remain unaddressed and have become even more daunting, and new challenges have emerged”.

We, therefore, need a social corrective along with the economic correctives to redress these challenges. Mere infusion of funds might not be enough unless the underlying social gaps and divisions remain in place. Barriers growing from caste and other identities, that have seemingly hampered progressive measures such as farmer’s cooperative movement in most parts of the country barring a few regions, need to be dismantled and ground created for collective action.

We have the resources and the ability to bring happiness to the life of our farmers. It would take persistent, continuous action but it is not impossible. The government needs to take bold steps to translate the good intentions into action to tackle the deficiencies. This would, however, require a strong political will and the need to develop a wide political consensus.

Time has perhaps come for us to consider putting in place a “Grow in India” programme to transform the socio-economic fabric of our agricultural sector as much as we need a “Make in India” programme.

I thank you again for inviting me here today and wish you successful deliberations.

Jai Hind.”